Keeping An Eye On Unit Labor Costs

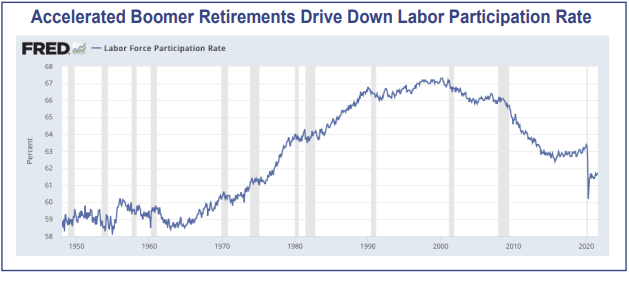

Over the last 18 months we have probably seen 4-5 years’ worth of Baby Boomer retirements – enough to drive down the labor participation rate by more than a full percentage point. Unlike many who have temporarily pulled out of the workforce, these folks are unlikely to return after the pandemic recedes, as travel and leisure activities now top their priority lists.

The U.S. economy has now entered a "transitory" adjustment period that stretches the meaning of the word. Over the next five years, we could see an elevated rate of wage inflation that might persist long after the present spate of supply-chain disruptions are resolved.

So far the Fed has not become overly concerned about the situation, because unit labor costs remain well-controlled, thanks in part to the long hours that still-active employees are putting in, and because some of the labor involved in generating revenue has been shifted to consumers. For example, when consumers do things online instead of over the phone, or pick up furniture as opposed to having it delivered. The switch to more labor-efficient business models is also helping – that’s what happens when you buy something on Amazon or opt for takeout instead of dining in.

Still, at some point businesses must either get to a sustainable level of staffing or automate to meet demand with the workers they currently have. Neither path will be easy. Automation means new software and new processes more often than it means dedicated machines that can replace people (such as in a factory). And it often requires substantial investment, though the price tag is falling with each passing year. The U.S. economy is in a bit of a Catch-22; the labor crunch is here and now, but many cost-effective automation solutions won’t show up until the problem has been largely sorted out.

Economic ImpactThe labor shortage is most acute in industries where revenue per employee is the lowest – primarily food service, retail, and hotels/casinos. And no surprise, this is also where wage pressures have been the greatest in recent months. While automation is neither cost-effective or practical here, higher wages may ultimately do the trick by enticing some retirees back into the workforce on a part-time basis. There’s a growing chance that selfdriving vehicle technology could free up large numbers of employed drivers (which could work in various service industries), but it’s unclear whether we’ll see any meaningful impact in the next five years. More likely, we’ll see significant, long-lasting inflation in the leisure segment. On the plus side, as wages in this segment are starting from a relatively low level, the overall impact on inflation could remain moderate, especially if other industries embrace automation.

In the current environment there is more acceptance for price increases, and to the extent that companies are able to pass along wage increases, corporate earnings remain poised to deliver long-term growth exceeding inflation by seven percentage points. Stock valuations, on the other hand, could shrink to reflect the fact that future earnings are worth less in today’s dollars when inflation runs at a higher rate. The effect is relatively modest when prices are climbing at a longterm rate of 5% or less, but above that level there tends to be more corporate "car-wrecks," and much like a credit-crunch, investors get overly cautious with valuations.

There is some risk this scenario could play out in the consumer discretionary segment. But with most leisure firms priced at relatively low multiples, the possibility of significant wage pressures is already priced in to some degree. Notably, the companies with larger market capitalizations fall into some combination of three categories: highly labor-efficient (Amazon, Tesla), proven pricing power (Nike, Starbucks), or discounters (TJX, Dollar General). This could help blunt any impact from higher-than-expected wages in the sector. In the case of Select Consumer Discretionary, the manager appears to be underweighting firms like McDonald’s where wage inflation or acute labor shortages could wreak havoc.

As such, we see the bigger risk being the Fed, which could become more hawkish if unit labor costs for the entire economy begin to grow at a faster rate. In a scenario like that, the best opportunities would likely include companies that are highly labor-efficient (think technology disruptors) and/or providers of automation software or equipment. We don’t anticipate making any major moves in that direction yet, but we’ll be keeping a close eye on wage inflation.

Third Quarter ReviewAmid blockbuster second-quarter earnings reports, investors continued to migrate toward blue-chip stocks during the third quarter – even as the Delta Covid strain led to another surge of hospitalized patients. An economic slowdown was anticipated but never materialized, thanks in part to inventory restocking and heavy leisure spending among vaccinated consumers. Instead, supply-chain constraints intensified, inflation picked up, and the Fed shifted its stance toward a less accommodative monetary policy.

The S&P 500 rose 0.6% for the three-month period, for a return of 15.9% year-to-date. While smaller stocks outperformed in September, the Russell 2000 still finished the quarter five percentage points behind the S&P 500, meaning the stock side of our portfolios saw a headwind again this quarter.

The Barclay’s Aggregate U.S. Bond Index finished the quarter nearly flat (0.1% return) despite growing wage pressures and rising inflation (the index is off 1.6% year-to-date). The Fed gets credit for that; during the quarter they recognized that pricing pressures might be more than transitory, and they walked back policy expectations in a way that kept bond investors comfortable. The income side of our blended portfolios, which includes some exposure to high-yield bonds (which tend to benefit with rising inflation), finished in-line with the Barclay’s Index. In our bond-only accounts, where we have relatively heavy high-yield exposure, we finished slightly ahead.

OutlookThe market may face some significant challenges in the fourth quarter. Republicans are okay with the $1.1 trillion infrastructure bill, but they see the $3.5 trillion stimulus package (and the taxes that go with it) creating more economic problems than it would solve. Their best hope for killing it is to force the Democrats to integrate a debt-limit suspension (or increase) with the $3.5 trillion dollar package, in hopes that moderate Democrats will refuse to go along, at which point both sides of the isle can get behind the $1.1 trillion infrastructure bill and a debt limit suspension (or increase) to go with it. The main risk for the market is that the Democrats attempt to go it alone but run out of time, risking a technical default for some Treasury bonds. A secondary risk is that the Democrats succeed in passing the infrastructure bill, the $3.5 trillion stimulus package and a debt limit suspension (or increase), but investors then decide to take profits in the 2021 tax year to avoid paying a higher longterm capital gain tax rate in 2022 or 2023.

Our strategy, for the most part, will be to do nothing – much like we did when the pandemic first hit. Our portfolios are in a reasonably balanced position, and we think they can weather any outcome, whether deflationary or inflationary. Solvable problems usually do end up getting solved at some point, and it rarely pays to compromise long-term positioning in order to deal with a very short-term problem. As for accounts that are holding Short-Term Treasury Bond Index, past market action suggests that while the stock market may take a hit from a threatened Treasury default, the Treasury bonds themselves may not react all that much, as the Fed’s got their back. So while we considered the option of distancing ourselves from Treasury Bonds by moving to Conservative Income Bond Fund (which holds mostly dollar-denominated corporates), it’s not clear that a move like that would help, and it might actually hurt.

Looking beyond these very short-term risks, it’s increasingly clear that the U.S. economy is emerging from the Delta wave intact, and that consumers appear willing to spend more freely than they have in decades. Expect corporate earnings to remain robust, perhaps providing a favorable backdrop that is strong enough to overcome any P/E shrinkage due to higher rates of inflation and/or increased corporate and capital gains tax rates.

We stand ready to tweak our portfolios as tax rates and inflation risks become clear. Under a lowerinflation / unchanged tax-rate outcome, we may opt for a modest increase in growth-stock exposure (much as we did with a recent change in our TE Select Model). Under a higher-inflation / higher taxrate scenario, we might look at a more significant overweight in financial stocks. In either case we expect to maintain interest-rate risk at modest levels in accounts that include an allocation to bond funds.

Sincerely,

Jack Bowers

President & Chief Investment Officer