Why A Major Federal Debt Crisis Could Be a Long Way Off

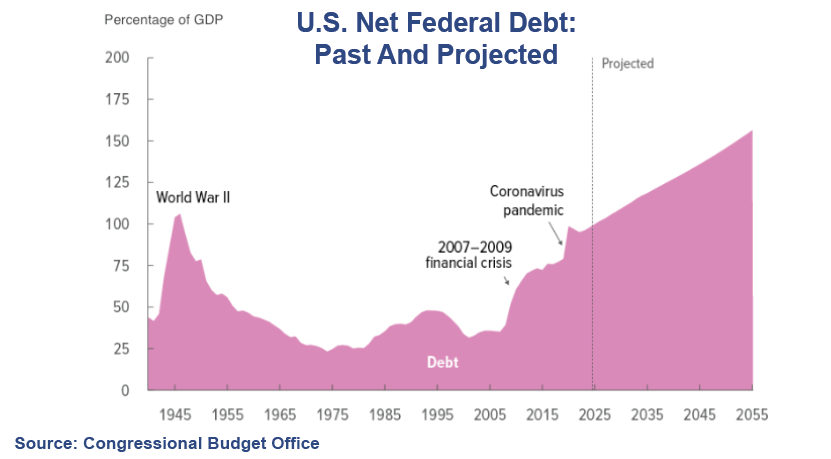

With the federal government spending like there’s no tomorrow, many investors fear a day of reckoning, but it’s hard to know when it might occur. If Congress can eventually bring annual federal deficits down from today’s 6-7% of GDP to around 3%, such an event might be entirely avoidable. If not, Treasury investors will demand sharply higher yields at some point, it’s just a question of when.

Fortunately, the U.S. is in a favorable economic situation that is buying us time. Some European countries with debt-to-GDP ratios similar to the U.S. (near the 100% level for net debt) are already being forced into making tough choices where taxes and spending are concerned. But here at home, the dollar is still relatively strong and the 10-year Treasury yield is in the 4-5% range. Following are the reasons why the global markets appear to be granting us a hall pass.

Higher GDP GrowthThe AI revolution is largely a domestic one, and it is benefiting U.S. GDP in two ways. First, with big potential to boost service-sector productivity, it has catalyzed a capital spending boom focused on data center construction and power generation. Second, assuming that non-farm productivity remains elevated between now and 2030, it is hard to see a scenario where GDP growth does not remain above 2%. This would be significantly higher than other developed nations, and it would likely boost tax revenue by 4-5% annually, making it easier to service the federal debt. Low Percentage of GDP Taxed

The U.S. does not have a value-added tax like Europe, Japan and Canada, so U.S. federal tax revenue runs well below its potential. In other words, our high deficits are a pro-growth choice, not because the U.S. is out of options and would risk economic harm trying to increase tax revenue (like much of Europe and Japan). In a pinch, an unpopular 5% federal GST (similar to what Canada has) could allow for servicing the federal debt in almost any scenario, with relatively little negative impact on the economy. Increasingly, Treasury Debt Is Domestically Owned

Despite high levels of debt, Japan has largely avoided a crisis because its federal debt is owned almost entirely by its citizens. With over 70% (and climbing) of U.S. Treasuries owned domestically, we are headed in a similar direction. In some ways we have the BRICS nations to thank for this. By trying hard to replace the dollar as a reserve currency, they are bearing the risk of other alternatives and reducing their role in the Treasury market, which could mute any interest-rate spikes that might occur heading into a crisis scenario.

By functioning somewhat like a corporate tax that encourages domestic manufacturing, and by generating a significant amount of tax revenue, tariffs are modestly reducing the federal deficit while encouraging a small amount GDP growth through reshoring. By doing this at a time when productivity is elevated, and when the economy is being boosted by heavy AI investment and the Wealth Effect, the inflation impact from tariffs has been relatively light, and the GDP headwind has been largely offset as well. Dollar Is Backed By More Than Creditworthiness

The U.S. economy produces goods and services that other countries need (technology, oil and gas, machinery, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, aircraft, food commodities), so there’s a limit to how far the dollar could fall if Treasuries were suddenly considered junk bonds. Furthermore, in any debt crisis there would likely be enough top-rated companies that corporate debt could serve as a stand-in for Treasuries. Benefits of Long-Term Investing Still Outweigh Risks

Most likely these factors will manage to avert a major crisis for more than 15 years, suggesting that those who continue their long-term investment strategy in the AI age will be rewarded. But investors should still be prepared for the possibility of ongoing mini-crises: progressively longer government shutdowns, surprise interest rate surges when Treasury auctions don’t go well, surprise tariff hikes, trade-related supply chain disruptions, and Fed interventions to stabilize the Treasury market. Even the upcoming Supreme Court decision on tariffs, which could happen anytime between now and summer, has potential to roil the markets.

The important thing to keep in perspective is that these events may be a necessary part of the process which ultimately leads to a long-term solution, and that the impact on inflation and corporate earnings will probably be limited. As long as you are maintaining an appropriate level of risk in your portfolio, and not panicking when you turn on the television or read the news reports, you’ll be in a better position to stick with your strategy and enjoy the benefits of longterm compounding.

Fourth Quarter ReviewInvestors worried about whether the Fed would follow through with anticipated rate cuts in the fourth quarter, and concerns mounted that the huge amount of capital being deployed into AI data-centers might not pay off with attractive returns in the event that corporate adoption of AI tools takes longer than expected. On top of that, rising interest rates in Japan once again put the squeeze on carry-trade bets, triggering a rout in speculative stocks and other aggressive bets including bitcoin. But in the end, the S&P 500 still managed to post a positive quarter thanks to an economy that continues to surprise on the upside, and because of an improving earnings outlook for 2026. The index rose 2.7% for the three-month period, for a 2025 total return of 17.9%.

The bond market was tame in comparison, barely reacting to the same inflation news that caused stocks to gyrate, and ignoring the selloff in private data center debt. The U.S. Aggregate Bond Index gained 1.1% for the quarter, finishing 2025 with a total return of 7.3% – its best showing since 2020.

On the stock side, our sector holdings outperformed. Our diversified portfolios trailed in some cases while performing on par with the S&P 500 in others. On the bond side, our emphasis on intermediate and short-maturity bonds provided performance that was similar to the U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, but with half the risk exposure in most cases.

Looking AheadWe are in an industrial revolution of sorts, one that likely justifies the enormous amount of capital investment. AI data centers are effectively new age "factories" that will make possible all kinds of automation while enabling higher wages through elevated productivity growth. It’s not unreasonable that Wall Street is questioning the ROI on this massive re-allocation of capital, because excess capacity can weigh on margins when the adoption of new technology turns out to be slower than expected. Still, the companies behind this revolution are both profitable and experienced technology players, and they are building powerful new tools that will likely enable above-average corporate earnings growth for many years to come. While some of these technology players might suffer if we end up with too much data-center capacity, it’s hard to see a scenario where the broad economy would lose out.

As for the stock market, with projected 2026 earnings growth for the S&P 500 currently standing at around 15%, the backdrop remains favorable. However, with the Fed nearing the end of its easing cycle, it’s possible that stock prices could lag earnings this coming year, with P/E ratios contracting rather than expanding as they’ve done for three years running. This wouldn’t necessarily suggest a negative return for stocks, but it could mean that the S&P 500 will end up with performance that is more on par with bonds in the year ahead.

Regarding the economy, between ongoing federal deficits and robust data-center investment, we’re unlikely to see a recession, even if a weak job market weighs on consumer spending. Robust productivity growth and lower oil prices are helping to keep inflation in check as tariffs get fully absorbed into the supply chain, holding open the possibility that the Fed will have room for another cut or two as the data rolls in. But negative surprises remain a possibility; we might see another government shutdown, and the Supreme Court could rule against some tariffs which might result in other tariffs being increased.

As for the stock side of our portfolios, we’re comfortable holding a mix of growth- and value oriented funds, though we may need to selectively reduce our exposure to smaller stocks. We may also need to put greater emphasis on less-volatile funds to maintain our risk targets at a time when the standard deviation of the S&P 500 is running at lower-than-usual levels. On the bond side we will likely stick with our short-to-intermediate approach, as the yield curve may grow steeper in the face of rising productivity and ongoing concerns surrounding federal debt levels.

Sincerely,

Jack Bowers

President & Chief Investment Officer